Victorian Supreme Court’s May 2018 Decision on Misleading or Deceptive Advertising between Telstra and Optus

When are ads, misleading or deceptive ads, as considered by the Australian Consumer Law?

We see the term, misleading or deceptive advertising, thrown around in the news. When we hang out with friends, watch movies at the cinemas, see large billboards attached on city buildings, or go into shopping malls, everywhere there are advertisements.

For some advertisements, they promise everything. And sometimes, we wonder, can it deliver what it promises? Is it really true?

We explore the law around misleading or deceptive advertising in the context of telecommunications. In a recent decision in Telstra Corporation Ltd v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] VSC 280, Robson J delivered this decision on 30 May 2018.

What Happened?

On 11 May 2018, Telstra applied for an interlocutory injunction to prevent Optus from circulating an advertisement.

The advertisement was described by the Court as follows:[1]

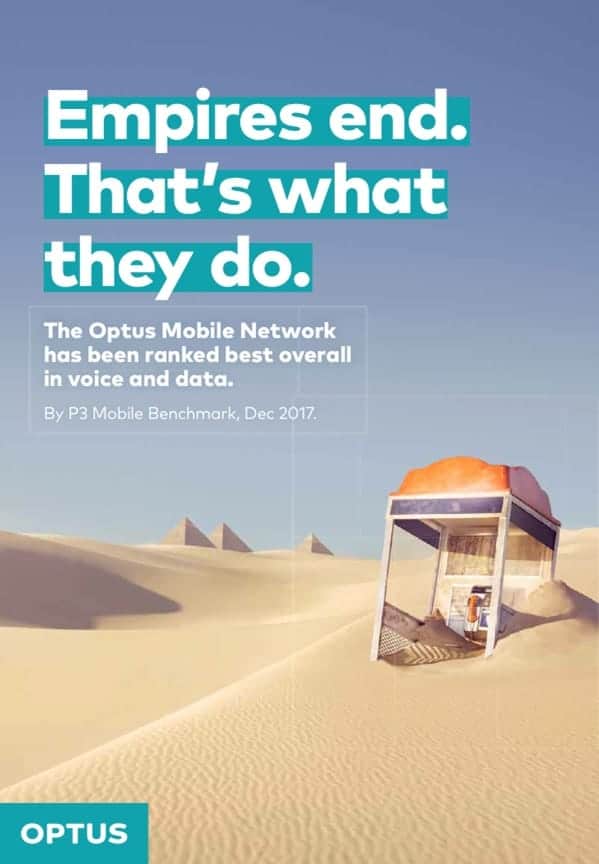

“’The advertisement features an image of a sand-duned desert landscape. In the background of the image appears a phone box, half-sunk and lopsided, like the decayed remains of a past area, sticking up conspicuously from the lone and level sands. In the background of the image appear several pyramids.

With its distinctive shape, and blue-and-orange colour scheme, the phone box is easily recognisable as a Telstra phone box of the type that was once commonplace on Australian streets.

Overlaid on the image is the headline: ‘Empires end. That’s what they do.’ Below that, in smaller print, in bold, appear these words: ‘The Optus Mobile Network has been ranked the best overall in voice and data.’ Below that in smaller, fainter print, appear these words: ‘By P3 Mobile Benchmark, Dec 2017.’”

A copy of the advertisement as cited in the decision as follows:

Source: Telstra Corporation Ltd v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2018] VSC 247 [2]. Here, Robson J described that ‘Optus has widely circulated an advertisement promoting its mobile network. The advertisement has appeared on large-format digital billboards at several sites in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. The advertisement has also appeared in the form of ‘online banner ads’”.

What was Telstra’s Claim?

Telstra claimed that by circulating the advertisement, Optus breached the following sections in the Australian Consumer Law (hereinafter ‘ACL’):

- section 18 (Misleading or deceptive conduct);[2]

- section 29(1)(b) (False or misleading representation about goods or service);[3] and

- section 29(1)(g) (False or misleading representations about goods or services).[4]

Primarily, Telstra argued that the advertisement conveyed the representation that:

- ‘there has been a significant and permanent change in the relationship between the Telstra and Optus mobile networks with Optus now undisputedly operating a better mobile network overall than Telstra’;[5] and

- ‘Optus [is] now undisputedly operating a better mobile network overall than Telstra.’[6]

Telstra’s First Claim

What did the Court Consider? Test of Misleading and Deceptive Advertising

Robson J considered in examining whether a conduct is misleading or deceptive was a ‘two-step process’.[7] For advertisements, the steps are as follows:

- whether the pleaded representation is conveyed by the advertisement;[8] and

- whether the representation conveyed is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive.[9]

Furthermore, an misleading or deceptive Advertising is also dependent on the audience.

For example, Robson J suggested that if the advertisement is conveyed to the public, it is important to identify ‘the class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct.’[10]

In this context, the class of consumer were ‘ordinary and reasonable people within the class of potential purchasers of mobile telephone services.’ [11]

What did the Court Decide? The Outcome

Robson J states that ‘the pleaded representation is not capable of arising from the impugned conduct of circulating the advertisement.’[12] This suggests that the Court could not determine Telstra’s arguments of alleged representations arising from Optus’ advertisements were the actual representations conveyed to the public.

At the same time, the Court also explained that the ‘advertisement does not convey to reasonable members of the identified class that the relative market positions of Telstra and Optus have undergone a permanent change.’[13]

In arriving to this conclusion, the Court reasoned that ‘it would be fanciful to image that the humorous image of a Telstra phone box in a desert landscape would persuade a reasonable person that Telstra’s strong position in he market has been permanently destroyed.’[14]

What about people who were unaware of the competition between Telstra and Optus?

For example, even if you were an ordinary and reasonable potential purchase of mobile telephone services, you might not know anything about Telstra or Optus. This is particularly the case if a potential purchaser is a recent immigrant to Australia.

The Courts attempted to tackle this question by concluding if a recently arrived immigrant considered purchasing a mobile telephone service without understanding the Australia market, they would still not be misled or deceived. [15]

So why did the Court exactly say that?

Robson J explained that for a recently arrived immigrant:

‘lacking an awareness of Telstra and Optus, he would not recognise the Telstra phone box in the sand, nor understand the rivalry to which the advertisement alludes.’[16]

Alternatively, because the recently arrived immigrant is on the far spectrums of this type of consumers, it might be that they would not be accounted for when coming to a decision. Robson J came to the opinion that:

‘As among the varied reactions which the advertisement must elicit from members of so broad a class, it may be that the view of this hypothetical immigrant is on the extreme end, such that the Court would be right to overlook it…. under section 18 of the ACL.’[17]

Telstra’s Second Claim

What did the Court Consider? Test of False or Misleading Conduct

Compared to section 18 (Misleading or Deceptive Conduct) of the ACL, section 29 (False or Misleading Representation about Goods or Service) while similar to section 18, leans towards the characteristics of ‘false’ or ‘misleading’ qualities.

The Court referred to Insight Radiology Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1406 and the summary points concerning section 29 of the ACL:

“(a) conduct is, or is likely to be, false or misleading if it tends to lead into error, even if there was no intention to mislead or deceive;

(b) whether conduct is, or is likely to be, false or misleading if it tends to lead into error, false or misleading must be determined objectively by reference to the class of people likely to be affected by the conduct;

(c) a court must ask whether or not a ‘not insignificant number’ of ‘ordinary’ members of that class of people would, or are likely to, be misled or deceived;

(d) the plaintiff need not demonstrate actual deception but conduct that may cause confusion or uncertainty is not necessarily ‘false or misleading.’”[18]

In considering section 29, Telstra raised two areas of law concerning sections 29(1)(b) and 29(1)(g).

Section 29(1)(b) of the ACL concerns:[19]

29 False or misleading representations abut goods or service

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotions by any means of the supply or use of goods or services: …

(b) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade.

Moreover, section 29(1)(g) of the ACL is referenced to:[20]

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services: …

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorships, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits.

What did the Court Decide? The Outcome

While Robson J accepted that Optus’ advertisement conveyed a representation that Optus’ mobile network was ‘better than Telstra’, for the purposes of section 29(1)(b) of the ACL, the advertisement did not suggest that it was “‘undisputedly’ better’”.[21]

At the same time, Telstra could not succeed in section 29(1)(g) of the ACL as the alleged representations by Optus did not reach the required level of detail and specificity required to satisfy the test. Telstra’s claim of Optus’ alleged representation was only referenced to the qualitative element of ‘better’ as the performance characteristic, and this was not sufficient. [22]

It seems to be suggested by Robson J that what was required for section 29 was the representation conveyed must be “that Optus’ network is undisputedly better than Telstra’s’”.[23]

Our Thoughts

In a battle between two telecommunication giants, this recent decision by the Victorian Supreme Court provides clarity towards the boundaries and scope of sections 18 and 29 of the ACL.

With greater certainty to how advertisements are interpreted alongside the law, in a globalising and technological age where marketing and presentation of goods and services become increasingly important, this should provide greater confidence for the Australian advertising industry. Find out more about about misleading or deceptive advertising on the ACCC – Australian Competition and Consumer Commission website.

If you have any concerns or queries concerning with misleading or deceptive advertising then AMK Law may be able to help in your consumer law matter.

Important disclaimer: The material contained in this publication is of a general nature only and it is not, nor is intended to be, legal advice. This publication is based on the law as it was prior to the date of you reading of it. If you wish to take any action based on the content of this publication, we recommend that you seek professional legal advice.

[1] Telstra Corporation Ltd v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] VSC 280 [3].

[2] Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) sch 2 (‘Australian Consumer Law’) s 18.

[3] Ibid s 29(1)(b).

[5] Telstra Corporation Ltd v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] VSC 280 [5].

[7] Ibid

[18] Insight Radiology Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1406 [143].

[19] Australian Consumer Law s 29(1)(b).